The Trifold Evolution of Christopher Nolan

Dividing the esteemed director's filmography into three phases

In my entire theatergoing history, two experiences stand out. Both involved leaving the theater with my mind blown. Both involved pouring over the details of the film I had just watched with rapt, geeky delight. And both films were directed by Christopher Nolan. To be precise, those films were The Prestige and Tenet.1

Yes, Nolan is one of my favorite directors, living or dead. His ability to push the boundaries of cinematic storytelling and explore existential concepts in unique ways is affecting on multiple levels.

Another reason I’ve liked Christopher Nolan is more personal, as it addresses a topic I write about often—i.e., the pornification of mainstream entertainers. In his body of work thus far, Nolan has avoided objectifying his actors through sexualized nudity or gratuitous depictions of sex.2 It’s not like he hasn’t had the opportunity: his narratives have involved femme fatales, prostitution, fornication, and hints at both rape and adultery. Even so, he has navigated these topics with relative restraint—something for which I am grateful.

(An important parenthetical statement must be made here. Oppenheimer, Nolan’s newest film, is rated R for “some sexuality, nudity, and language.” According to The Guardian, this movie “features prolonged full nudity for Murphy and Florence Pugh, who plays Oppenheimer’s ex-fiancee, as well as sex, and there are complicated scenes with Emily Blunt, who plays his wife, ‘that [are] pretty heavy’.” If these statements are accurate, and it’s hard to believe they aren’t, Oppenheimer represents a thoroughly disappointing step down for Nolan.)

Three Phases of Parables

In evaluating Nolan’s oeuvre, the book Deep Focus: Film and Theology in Dialogue proposes that Nolan’s movies function as modern-day parables:3

Indeed, to repeat our earlier description of film as parable (chap. 7), [Nolan’s] movies (1) are brief stories rooted in everyday life; (2) are compelling (“exciting”) stories, arresting the attention of their audience by inviting their listeners to see reality from a new angle; (3) do not primarily convey information but, by the more indirect communication of the metaphoric process, invite their audiences to discover spiritual truth or meaning as the human condition is portrayed; and (4) function subversively, undermining certain contemporary attitudes, beliefs, and/or authority (disorienting) even while inviting, teasing, or provoking new truth and/or transcendental insight (reorienting). (210)

There is a sense in which Nolan has a fairly cohesive filmography; rarely has he strayed from the conceptual wells of time and memory, and how they affect one’s perception of reality.

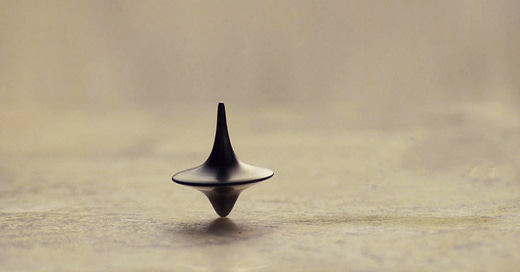

Nevertheless, while working on my review of Tenet back in 2020, I came to a realization: Christopher Nolan has gone through what we might call three phases as a director, each with its own distinct characteristics. We might label these three phases as follows:

“Before his time” (1989 - 1999)

“It’s about time” (2000 - 2014)

“Time, times, and half a time” (2014 - Present)

In the first phase, Nolan struggled to make it into the big leagues. In the second phase, Nolan solidified his methods, expanded his mythemes, and established himself as a force to be reckoned with. His third phase is characterized by two particular shifts in storytelling techniques.

Last year, Cinema Faith published my detailed analysis of each of these phases in a piece entitled Christopher Nolan in Three Acts. This is a lengthy exploration of the esteemed auteur’s entire collection of feature-length films to date.4

So if you wish to revisit Nolan’s work to date, grab a Diet Coke, take a does of Somnacin, and prepare to perceive that which transcends dimensions of time and space. You’re about to board a train that will take you far away.

In other words, we have a lot of ground to cover.

Both of these films have gotten better with each successive viewing—although I will admit to posting the following comment on social media after watching Tenet a second time: “Last night was still the first night I ever prayed for help with better understanding a movie. It is definitely dense. Like a pound cake made out of a black hole.”

The closest he has gotten thus far is a naked corpse in Insomnia and a post-coitus scene in The Dark Knight Rises, which involves a romantic turn that makes little narrative sense.

Published in 2017, this book examines Nolan’s work up to and including Dunkirk.

The release of Oppenheimer could, of course, usher in a fourth phase, or create the need for a recategorization of the third phase. Time will tell.